Mary Anne Eade's Journal of a tour recounts a journey made in the spring of 1802, in the company of her husband William. Beginning in London, Eade's itinerary takes in the midlands, north Wales, Dublin, and County Wicklow, before returning to north London. Sympathetic to Wales throughout, this tour is characterised both by an awareness of internal British boundaries – Wales is 'another country, tho' not another island' (f. 19v) – and a joyful sense of celebration. Harp music heard at the border town of Oswestry prompts Eade's elation at the idea of crossing into 'that land of wonders I had so long wished without hope to contemplate'.

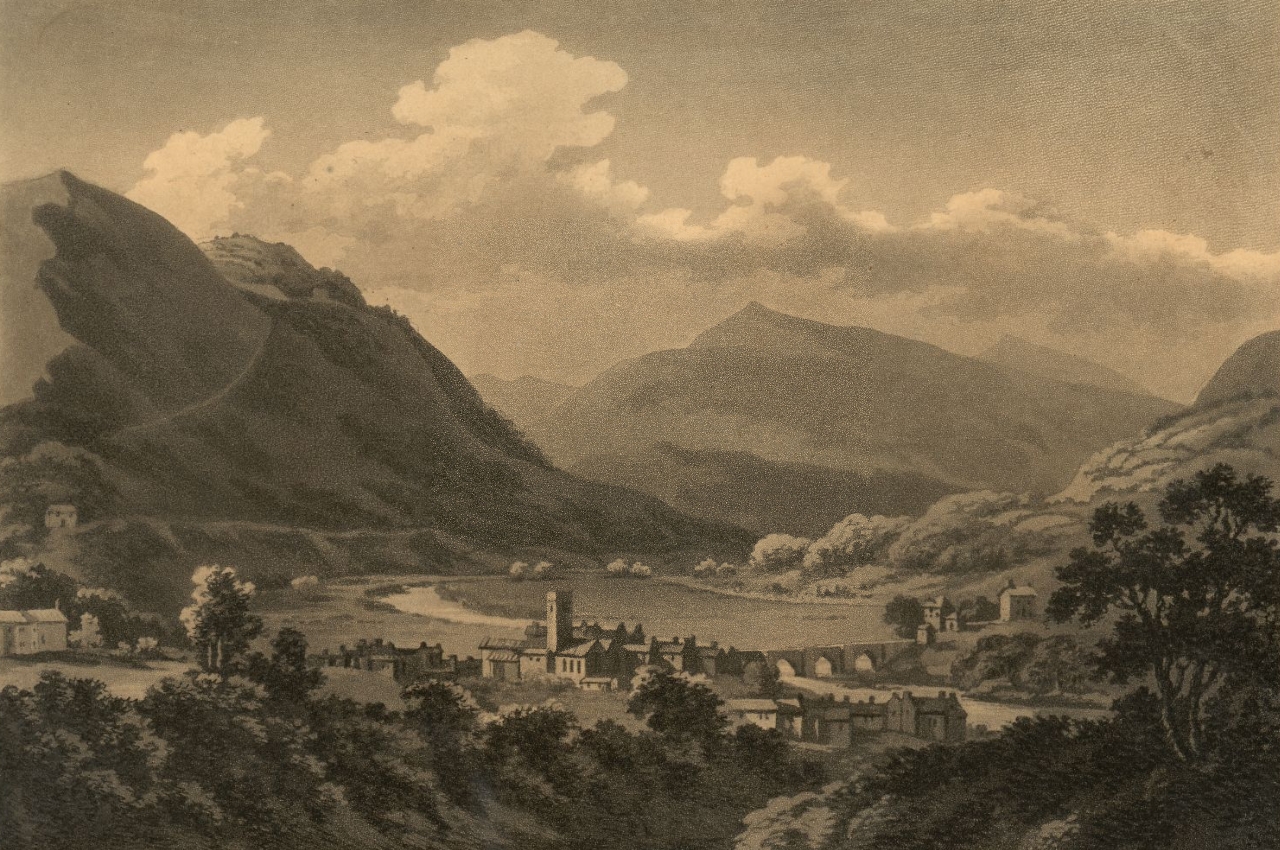

Eade came from a London merchant family background, and belongs among the many home tourists writing in this period who are not known to us today beyond their surviving manuscript accounts. Although she therefore has no profile as a writer beyond this work, her narrative is articulate and readable, full of engaging detail and novelistic moments. Her skill in recounting events on the tour is well-illustrated by sections set in Llangollen [fig. 1], where the Eades are served by a French waiter (f. 22r) and where an expedition to Dinas Brân, the castle overlooking the town, takes an entertaining and melodramatic twist. Eade is similarly appealing on the interior life of the home tourist, representing the displacements of travel as a disturbed emotional state in a passage on waiting for the Irish ferry at Holyhead:

my mind during this interval naturally dwelt on all those dear friends from whom the boundless ocean was so soon to separate me … the idea of having the rolling sea between us was so new & so strange as to appear to me quite frightful (f. 33v).

Later in the tour, the material challenges of travel – dirt, discomfort, poor weather – lead her to wryly acknowledge, 'I am not a thorough traveller yet' (f. 57v).

Eade's tour is particularly notable for its account of Ireland, in which she outlines the sociable and touristic contexts of turn-of-the-century Dublin before making a tour of Wicklow to the south. Her account includes well-known picturesque locations such as the River Dargle and the Powerscourt estate [fig. 2]. But Eade also sets these scenes, which she describes as 'formed to be the abode of quiet retirement' (f. 43v), alongside the 'late rebellion' – the United Irish uprising of 1798, which had recently devastated this region. Just four years later, the events of 1798 have become incorporated into the tourist trail; their trauma part of and visible in the landscape.

Fragments of internal evidence about Eade's life and situation make this a rich tour for still other reasons. Pleasure is, predictably, an important part of a trip made 'in quest of new beauties', but the personal elements and emotional narratives of this text particularly stand out. A short preface, written by her husband, and dated March 1803, frames this tour and announces that Eade (b. 1778) has since died. The manuscript consequently becomes a powerful personal memorial, an object of grief, as well as an account of a journey that, aside from the text, 'now appears like a pleasing vision, impress'd indeed strongly upon the imagination, but without reality' (f. ii). It was also written as a personal document to a younger sister, Eliza (b. 1780), in response to her (untraced) tour of south Wales – not just an extended postcard, then, but also a form of gift exchange. Eade explicitly recognises that writing with a particular recipient in mind shapes both the literary aspect of her tour and her actual experience of travel on the road: 'I finish my little journal of a most delightful tour with regret because in finishing it I conclude a long imaginary conversation with you; which has possessed many charms for me' (f. 74r).

Note on the source text:

Aside from William Eade's short preface, the manuscript source is written in Mary Anne Eade's generally legible hand, with relatively few emendations. At over 23,000 words – partly because it also features an Irish tour – this text is one of the longer Welsh manuscript tours included in our edition.